A while back, I had the excellent good fortune to have a really cool conversation with author, poet, and all-around cool person Marie Marshall. Happily, when I got tired of talking about myself, Marie was kind enough to let me ask her a bunch of questions, too, which I was eager to do. A poet by nature, she also dabbles in erotica, she published a tribute to Gene Roddenberry, and she wrote a novel about a female gladiator! She also lives in Scotland, a home of which, if I didn’t love Portland, Oregon so much, I’d be supremely jealous. So I was thrilled to chat with her via email.

This was our conversation.

When you first started writing, what were you writing — and why were you writing it?

I started writing in about 2003. I started relatively late, being in my forties, and right out of the blue. No special grounding in writing, no creative writing course, nothing. I decided to go in for a short story competition — it was rather an unusual one because entrants had to finish a story which had been started by a famous writer, and I chose to finish one started by Joanne Harris about a woman who falls in love with a tree. It wasn’t an easy exercise; I guess anyone can have an idea of how to finish off a plot, but to be able to graft it onto an existing introduction so that the join or seam between the two is invisible is another matter. I had to absorb something of Joanne Harris’s style in order for it to work. I didn’t win, but doing it put into my mind the idea that I could write. I enjoyed it so much.

Anyhow, believe it or not, I continued from that point by writing erotica. I can’t honestly remember the circumstances but I was reading some and it was really dire. I wondered whether I could do better. Turned out I could.

When did you first start taking yourself seriously as a writer? And, okay, a lot of us still don’t take ourselves seriously as writers, because where’s the fun in that? So I suppose I mean, when did you first start trying to publish things? What drove you to send work out?

It’s difficult to say when I started to take myself seriously as a writer. I think there came a point in writing erotica when the story became more important than simply “writing dirty,” otherwise what was the point. Not that I ever did simply “write dirty.” The thing about sex is that it’s part of life, not an end in itself, and things happen while it’s going on — people get cramps, they laugh, they lose time, they get overcome with emotion and cry, all sorts of things like that. I recall writing a story called The Invisible Woman, the premise of which was a woman who had had cosmetic surgery to correct a disfigurement, and her later meeting a nurse who had befriended her around the time of her operation. Originally I had intended this to be an erotic story, but instead it seemed right to focus on other aspects, such as how a person defines herself, and in the end there was one unexpected kiss and that was that. I guess that was the point at which I became a mainstream writer.

About the same time a friend gave me an idea for a novel — in fact she said little more than, “You should write a story about a female gladiator,” and at the time Rome was “hot,” what with the film Gladiator and all — and what came out of that was my novel Lupa, which wasn’t completely about a female gladiator by the time I got to the end. I wanted to nod at the “sword-and-sandal” genre but not to fall prey to its clichés (er… “fall prey”… that’s a cliché… oh dear). I completed that in 2004, but it took until 2012 to get it published.

Everything seemed to gel around 2004/2005. I started writing poetry, started sending it to magazines and got one published in a magazine fairly quickly. I started writing macabre stories for a competition run by the Winter Words literary festival in Scotland and became one of their regularly-featured writers, having my stories read to an audience by a professional actor.

What actually drove me to try to get things published is another matter. I really can’t remember. Except perhaps I wondered what was the point of writing unless I tried to get other people to read? Although I have contemplated writing poetry that no one else will read and burying it in the ground (as an artistic experiment), I have always been aware that to create any work of art is to attempt to communicate. Once a story or a poem “leaves” me it becomes the experience of the reader. Was it Roland Barthes who wrote of “the death of the author?” That takes it to an extreme, but basically I felt that if it was worth writing it was worth trying to get it “out there.” Also, if I am honest, and bearing in mind that these days it is so easy to get things “out there” by blogging, self-publishing, and so on, I have always felt that persuading someone else to publish my work legitimizes it, confers credibility on it. I try to write to a standard which I would like to read, so being published confirms that I have probably achieved that. I hope that doesn’t sound complacent or pompous.

I love your bio on your Marie Marshall website. It’s quite impressionistic, all glimpses and moments. What made you decide to approach your bio that way?

Basically because I am a boring person who has led an unremarkable life. Also I guess it turned my bio into an exercise in creative writing. And it worked.

You have how many blogs and web projects now? Two personal blogs and the zen space site. Your Lithopoesis project. Probably more I don’t even know about. Is this an attention deficiency, or do you just never sleep? What drives you to tackle so many projects?

It’s funny, but it doesn’t seem a lot. I have my main web site, which I try to keep as “clean” and professional as possible. It has a blog section on which I post literary news, the occasional review, interview, or story from time to time, just to keep the content fresh. Then I have the poetry blog on which I post a very short burst of poetry every day; this helps to maintain a little self-discipline, it hones my ability to express things economically.

The Lithopoesis site is an archive of a poetry experiment I conducted in 2010. As such it’s not something I add to. As for the zen space, I guess that’s a kind of open e-zine rather than a blog — it’s for other people’s writing rather than my own — as being an editor is another string to my bow.

Somewhere I do have another blog, on which I used to post humorous pieces, anarchist rants, and essays on English folk dancing. You heard me. Basically that is dormant at present.

With all those projects and all the writing you do, what do you do when you find yourself overextended? How do you unwind?

I eat, I sleep, I listen to cricket commentary on the radio, I watch escapist TV — currently I’m following a re-run of Dexter — and if all else fails I have a nervous breakdown.

You seem to love formal poetry. Sonnets, haiku, block poems…. Is it a restraint thing, or is there some other reason you’re drawn to form?

When I started writing poetry it was mainly free verse, except for the odd one here and there in which I tried to use metre and rhyme. The more I wrote free verse, the more I became conscious of such things as the way it looked on the page, the sounds the words made, and the rhythm. I began to look for, find, and deliberately give my poetry internal structures, if not recognized form at that stage.

I think at some point I began to realize that free verse had been around for a relatively short time, and that most poetry, certainly in English, was overwhelmingly formal. I began to see that far from constricting poetic expression, it could lend enormous power — it had done so for the likes of Shakespeare, Shelley, Dylan Thomas. I wanted to see whether I could use formal poetry to say things without the form dictating to me. I was looking for that technical power, if you like, that is almost unnoticed except in its effect. I began to write English sonnets. I loved iambic pentameter; I realised that it was based on the rhythm of everyday speech, that each line was easily covered by a single breath, that each line was compact enough to be memorable for an actor in classical Greek drama, and most importantly I learned that it was a ripple not the thud of a jackhammer. I became fairly well known for my sonnets and joined the editorial team for Describe Adonis Press of Canada. We’re currently working on the twenty-first century’s first major anthology of contemporary sonnets.

I have even “invented” poetic forms — the “loose sapphic,” for example — but I have to say I wasn’t actually trying to. I was simply looking for a good way of saying something, of more than saying something. I’m wary of the vogue for inventing poetic forms, because the result can be very contrived, more often than not.

It was at that point that I said something which I know is controversial. Referring to poetry, I said, “I’ve proved I can draw — now I’m entitled to pickle a shark and call it ‘art’.” I must point out I was speaking about myself. Just as in art there are people who leap in without learning basic draughtsmanship, or people like Andy Warhol who were rather bad at sketching but came up with amazing ideas in conceptual art, so there are poets who never so much as tried to rhyme “moon” and “tune” but who write staggeringly innovative free, avant-garde, or experimental poetry. I admit that. I was talking about myself. I guess I needed that grounding in self-discipline. I now mainly write what would be regarded as “free verse,” but inside I have what I hope is a kind of self-discipline. I call it discipline rather than “restraint” as you did in your question, because I can also let my hair down in free verse and “go nuts.”

I don’t know what the result of all this is, except maybe as a writer of free verse I am not afraid to write deliberately long lines. I know — I think I have been left with a sense of the meaninglessness of the Chinese walls between the various types of poetry. There is just poetry, a means of saying more than you can in prose, and with fewer words — a way of exploring the mystery of human consciousness and perception with words.

Your novel, Lupa, is published through P’kaboo Publishers in South Africa. You live in Scotland. What’s it like working with a publisher some 6,000 miles away?

Firstly it is great to have a publisher anywhere in the world, even a small press such as P’kaboo, that shows faith in a book. I could so easily have gone down the road of self-publishing, or applied to one of these publishing houses that offer author-subsidised publishing. I chose not to, even though I am confident of the literary worth of my two (so far) novels. It’s all to do with the legitimizing factor I mentioned before with regard to poetry. P’kaboo offered me a commercial contract and I said yes. I have to say that most of the hard work has been on the part of P’kaboo and my agent — they have been working tirelessly to promote Lupa, with only limited success. But at least, as Lyz Russo from P’kaboo said to me, I’m ‘on a moving vehicle’.

These days the world is a much smaller place, so I could say what’s six thousand miles? We have the internet, email, yadda yadda. All the editing, final layout, proofing, etc., was done by email and without any problem. I think that would have been the same if the publisher had been twenty miles down the road. The novel is available via Amazon, and there’s a Kindle version. Of course it would be great if the novel could be taken up by a publisher with more commercial clout — there’s provision for this in my contract with P’kaboo — but I couldn’t have wished for a more attentive, more supportive publisher.

My second novel, The Everywhen Angels, is currently sitting with a larger publisher in the UK, who asked to see the manuscript. For all I know it may be sitting in the “slush pile,” but at least being asked to send in a complete manuscript to a commercial publisher is legitimizing in itself, a sign of being taken seriously as an author.

I’m going to ask you a variation of the desert island question: Your house is burning down (touch wood), and you have time to grab just three books. Everyone is out and safe, your furniture and photo albums exist in some magic bubble so they won’t get destroyed — it’s just down to the bookshelves now. And it’s not the end of the world, so you can always buy new copies of the books that do burn. So which three irreplaceable books would you save?

Oh dear, this is a tricky one, because as you say just about any book you can mention can be replaced, and even some of the world’s rarer books exist in Project Gutenberg on the internet. I’m tempted to cite a relatively modern book that is out-of-print, such as Colin Thubron’s Emperor — a novel about Constantine — but on the other hand, although I enjoyed reading it I would not necessary want especially to save it from a fire. Same with David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus. Even a classic novel that I love — To Kill a Mockingbird — is easy to find a replacement for. So here are my three…

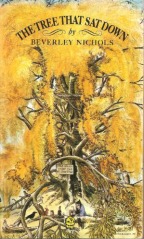

When I was little I had a hardback copy of Beverley Nichols’ The Tree That Sat Down. It was published in 1945 as the first novel in a trilogy of whimsical fantasies set in a forest full of anthropomorphic characters. The protagonist is a girl called Judy who, with her grandmother Old Judy, keeps a shop in the roots of an old tree, from which she sells goods to the talking animals in the forest. Her rival is a boy called Sam who, with his grandfather Old Sam, keeps a shop in the remains of a Model T Ford. Sam is boorish and mean-spirited; he is an unscrupulous petty-capitalist entrepreneur who cheats his trusting customers at every turn. Given my radical politics, it is unusual that I ended up sympathizing with Sam. An attempt is made on Judy’s life and Sam is implicated. He ends up on trial for his life, handcuffed by Constable Monkey, brought before Mr Justice Owl, questioned by Mr Tortoise as prosecuting lawyer. Eventually, as a great storm begins to rise, as Judy takes pity on Sam and shouts an unheard petition into the wind to whatever powers may be, he is saved by supernatural intervention. However, what drew me to his ‘side’ was the nature of the trial. The court was prejudiced against him because all the animals had found out that he was a cheat. There was no defending counsel. The plot to kill Judy had been orchestrated by Miss Smith, the witch, who had also made the poison. The task of delivering it to Judy had been given to Mr Bruno, the bear, who had turned himself in. Sam had been terrified, and had been persuaded into complicity by Miss Smith’s eldritch blandishments — and now Miss Smith and Mr Bruno appeared as witnesses for the prosecution. I longed to be his defense council, I was sure I could have got him acquitted! Instead I went back to the beginning of the book and,

When I was little I had a hardback copy of Beverley Nichols’ The Tree That Sat Down. It was published in 1945 as the first novel in a trilogy of whimsical fantasies set in a forest full of anthropomorphic characters. The protagonist is a girl called Judy who, with her grandmother Old Judy, keeps a shop in the roots of an old tree, from which she sells goods to the talking animals in the forest. Her rival is a boy called Sam who, with his grandfather Old Sam, keeps a shop in the remains of a Model T Ford. Sam is boorish and mean-spirited; he is an unscrupulous petty-capitalist entrepreneur who cheats his trusting customers at every turn. Given my radical politics, it is unusual that I ended up sympathizing with Sam. An attempt is made on Judy’s life and Sam is implicated. He ends up on trial for his life, handcuffed by Constable Monkey, brought before Mr Justice Owl, questioned by Mr Tortoise as prosecuting lawyer. Eventually, as a great storm begins to rise, as Judy takes pity on Sam and shouts an unheard petition into the wind to whatever powers may be, he is saved by supernatural intervention. However, what drew me to his ‘side’ was the nature of the trial. The court was prejudiced against him because all the animals had found out that he was a cheat. There was no defending counsel. The plot to kill Judy had been orchestrated by Miss Smith, the witch, who had also made the poison. The task of delivering it to Judy had been given to Mr Bruno, the bear, who had turned himself in. Sam had been terrified, and had been persuaded into complicity by Miss Smith’s eldritch blandishments — and now Miss Smith and Mr Bruno appeared as witnesses for the prosecution. I longed to be his defense council, I was sure I could have got him acquitted! Instead I went back to the beginning of the book and,  with pen and ink, began to rewrite Sam from his first entrance, determined to alter the whole book in his favour. I only got as far as the first three or four pages which became totally defaced. I think that copy of the book is in a box somewhere now. I’d like to have it with me so I can shake my head and laugh.

with pen and ink, began to rewrite Sam from his first entrance, determined to alter the whole book in his favour. I only got as far as the first three or four pages which became totally defaced. I think that copy of the book is in a box somewhere now. I’d like to have it with me so I can shake my head and laugh.

Second choice. In English literature the boarding school is iconic, from Tom Brown’s Schooldays to Harry Potter. I like fiction that subverts its iconic stature. I was thinking first of all of Rudyard Kipling’s Stalky & Co, but that book’s subversion is gentle and subtle. In the 1950s a series of – what? articles? stories? fictional memoirs? — began to appear in a magazine called The Young Elizabethan. They claimed to be from the pen of Nigel Molesworth, a semi-literate schoolboy at a seedy, third-rate boarding school called St Custards. They were in fact written by humourist Geoffrey Willans and illustrated by cartoonist Ronald Searle — if I tell you that Searle was responsible for the original St Trinians cartoons you’ll appreciate the level of the humour. It is totally subversive, totally iconoclastic, and bloody hilarious. The pieces were eventually collected together into a  volume called The Compleet Molesworth (sic). I think my copy is in the same box as The Tree That Sat Down…

volume called The Compleet Molesworth (sic). I think my copy is in the same box as The Tree That Sat Down…

Lastly — and let’s be serious — Young Stalin, the biographical work by Simon Sebag-Montefiore. It is an utterly fascinating book in which Dzhugashvili the seminarian, Dzhugashvili the poet, Dzhugashvili the swashbuckling bandit is seen growing towards Stalin the plausible father-figure, the dictator, and the monster that history has proved him to be. It’s eminently readable, and something that no serious student or lay enthusiast of modern history ought to be without.

Marie Marshall is a poet and writer. Her books include the novel Lupa and the poetry collections Naked in the Sea and the forthcoming I Am Not a Fish.

You can find out more about Marie at her website; you can find out more about the novel Lupa at P’kaboo Publishers.

Read some of Marie’s poetry at kvenna ráð.

This was a fun process, Sam, and I like it very much now it’s on the page. By the way – the Vermeer – I’d say ‘mystique’ rather than ‘anonymity’. I employ that picture because it inspired one of my ‘Pearl’ poems back in 2009/10:

You were once a grain of sand

that stuck in my heart

I secreted love around you

And now there you hang

catching dayshine from a southlight

They say that a woman

no matter how much clothing she wears

is naked the moment she puts on pearls

your glance and your half-smile

tell me they are wise

A bit ‘twee’ compared to my later work, but… well… y’know…

🙂

M.

Hurray! I had fun with this, too!

Also, “Girl with a Pearl Earring”? Nice choice for your mystique! Have you seen that painting in person? It is utterly stunning. Vermeer is just unearthly. 🙂

No I haven’t seen it, but I would love to.

Reblogged this on the red ant and commented:

Interview with one of our authors, Marie Marshall of “Lupa” and “Naked in the Sea”. She also contributed stories to “Mercury Silver”.

🙂 If nobody minds, I took the liberty of reblogging this…

Excellent! I don’t mind at all! 🙂

Thanks!

Neither do I. 🙂

2015 and there is still click-through from this post. Thanks, Samuel!

It was my pleasure!

I have moved on, by the way. I now like to use a pic of the Log Lady from ‘Twin Peaks’ rather than the Vermeer. 😀