I’ve done photo stories before (here, here, and here), but this one is a little different: this one involves two photos.

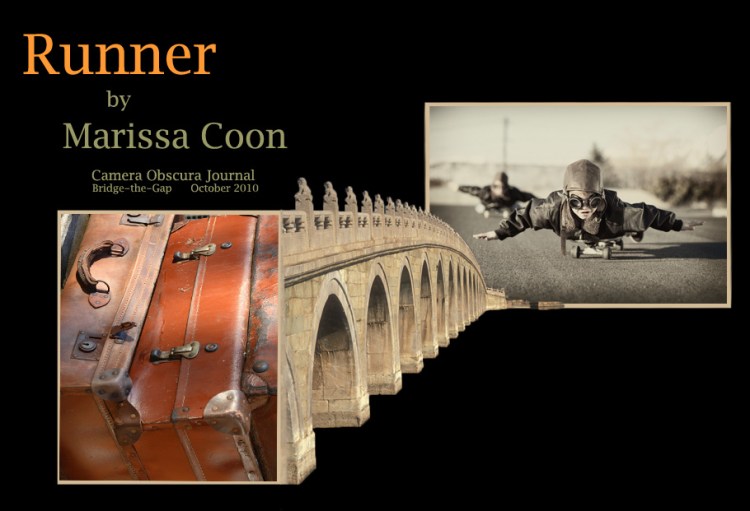

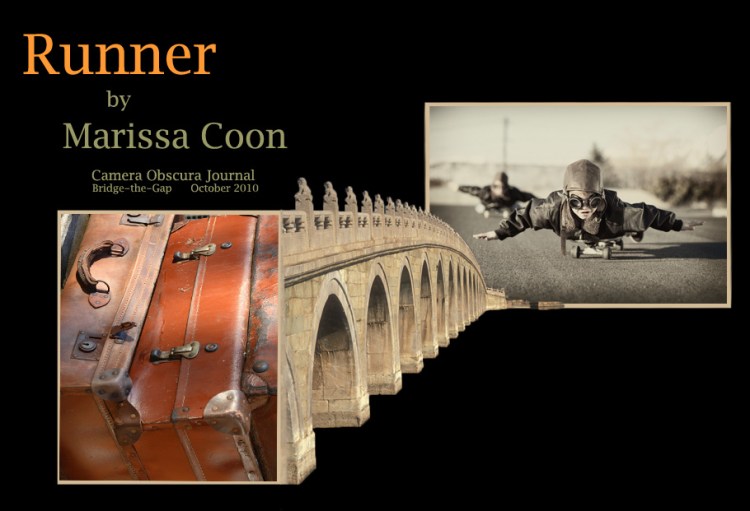

I’ll explain more below, but just so you know up front why I’m using two pictures, the idea here is to get from the picture on the left to the picture on the right — the suitcases to the kid.

So, here we go.

I was eight when I first came up with the idea, but I’d turned nine before I realized I could actually do it. It started when I found the old suitcases wedged into the hall closet between my bedroom and my mother’s. They were behind the vacuum cleaner, under a coat and an old wool blanket that made my small forearms itch. Boxy things, cracked leather and half-rusted catches. One of them was missing a handle. But they were sturdy, made for moving — for moving on. Those two suitcases were hope that smelled like mildew, and I loved them.

But it was just an idea, the same childish dream any kid has from time to time. I was more interested in the suitcases themselves than in the freedom they hinted at, which is why I kept returning to them on the weekends, while my mother was off at one job or another. I couldn’t do much but look at them, because the catches on one were rusted shut, and the other one was locked. But after a few months, I started spending my weekends rummaging through drawers in the kitchen, the bathroom, my mother’s bedroom, and eventually, I found a small glass candy dish full of old keys. I took them out one afternoon a little after my ninth birthday and started on the locked suitcase, one key at a time. It took me ten minutes to find the right key, but then the case fell open like an old book, and inside was the most remarkable thing I’d ever seen: a round leather cap lined in fur and attached to a pair and thick round goggles.

I touched the cap — it felt like an old glove, soft as a pillowcase and pliant as a handkerchief. I lifted it over my head. the weight of the goggles pulled the cap forward over my face so my nose smelled soft wool and sweat. I lifted the goggles over my eyes but they were huge, spanned halfway to my ears. I studied them until I figured out how to adjust the straps, and soon I had the lenses snug across my nose and the strap tight over cap on my head. I went into the bathroom and stood on the stool at the sink to behold myself. I looked fierce, like a crazy person, some antique combination of an astronaut and one of those insane bikers on the Mad Max movies. I felt daring, reckless, powerful, prepared for anything. I ran into my bedroom with the goggles and cap still on, whipped through the hangers in my closet and found the leather jacket my uncle had given me the year before. I put it on and raced back into the hall, across to the bathroom. I put my hands on my hips, my elbows jutting courageously outward. I sucked in air and pushed out my chest. I was a freaking superhero. I could face anything, go anywhere, escape it all.

From then on I spent all my spare time researching and planning. The school librarians loved me, then decided I was a little strange, and finally stopped paying me any attention. I learned that the cap I’d found was an aviator helmet from one of the World Wars; they called it a Snoopy Hat, and sure enough, I did remember seeing the dog wearing one in those cartoons. I figured my grandfather wore it, though I still don’t know which grandfather — both had been dead for ages. But I had inherited adventure, I knew that much, and I was ready to fly.

I made my mom buy me spiral notebooks in bulk — I said I had a lot of homework, and she never believed otherwise. I filled those things with supply lists, sketches, maps, timelines, anything I could think of. I was methodical. I was detailed. I was going to be prepared.

So I was eleven by the time I actually started the process. Most of the plan was mental preparedness: knowing where I was going, how I’d get there, what to do in various emergencies. But the hard work was collecting the supplies. I didn’t get much of an allowance, and it’s not like I had much time to shop by myself. I was alone plenty — that was part of the problem — but getting around by myself meant riding my bike or my skateboard, and there’s only so much I can carry on either of those things.

Still, a lot of the gear I was able to pick up in junk shops, root from trash bins, or dig out of my own mother’s utility room, where she kept some of the things my dad or my uncle had left behind, stashed up on the shelves over the washing machine and the water heater.

You’re probably thinking I was just another runaway, that I couldn’t possibly need all that much anyway. I’d be like those Calvin & Hobbes cartoons, where I’d stuff my backpack with comic books and tuna fish sandwiches and take off for an afternoon, maybe a night out under the stars, shuddering in my back yard. In some respects, you’re right — I did spend some evenings hiding under the back deck of our trailer, and one time I stayed out the whole night, the soft cap on with the goggles pushed up onto my forehead, my mother frantic on the old boards above my head, crying into the darkness and hoping I could hear her over the traffic on the nearby highway. Hoping I hadn’t wandered that direction and gotten hit or picked up by a pervert. But I’d had no intention of doing that, really. For one thing, the highway was too obvious an escape route. I would need to sneak through the woods and along the creek bed and get far enough away from town that passing cars wouldn’t potentially contain a someone who would recognize me. And for another thing, this night out under the deck was just a practice run: I’d wanted to see if I could sleep on the ground, just an old jacket for a pillow, huddled in woodrot and dirt.

I could. I was a pro. I had aviator blood. And my mother fed me cinnamon rolls, not those crap honey buns from the grocery store but real homemade rolls fresh from the Pilsbury can.

This was in the early spring, I think March — I forget what day, but it around the time of my birthday. The weather was great, a little windy but nice and warm in the day and not too cold at night, at least not once I packed that itchy wool blanket from the closet. So I decided to wait just another week or so. I would leave in April, warm enough at night to sleep comfortably but long before the exhausting heat of summer. That would give me maybe two good months on the road before I had to escape the Texas sun during the day. And by then, I figured, I’d be almost to Canada, so I could just keep on going if I wanted to. It was colder in Canada, even in the summer.

That year, Easter was in April, and our school let off for Good Friday but my mom still had to work. It was perfect. I had pried open the catches on the other suitcase and figured a way to tie it shut with shoelaces, and I’d already packed both the suitcases with most of what I’d need: a map of North America I cut out of an atlas at school, a flashlight and two extra batteries, a set of silverware from the kitchen and a few paper plates, one of my mom’s lighters, the pocket knife my uncle had given me, about fifteen dollars I’d collected from my mom’s purse and coins in the couch, and yeah, a few Hardy Boys books, because even though books are heavy, those Hardy Boys seemed to know a thing or two about surviving.

I’d been asking my mom to pack granola bars in my lunches since the beginning of the school year, and half the time I’d skip them and bring them back home, so I had a good stockpile built up. I filled my thermos with kool-aid and took a bottle of water from the fridge. I had my pillow, that old wool blanket, a change of clothes, my leather jacket even though I wouldn’t need it until Canada, and the Snoopy Hat and goggles. I was ready.

On Good Friday, I hauled out everything and dragged it to the front door. I had thought to ride my bike because I figured I’d make better time that way, but I couldn’t balance both those suitcases on the handlebars, so I gave up and leaned the bike against the trailer and got my skateboard instead.

It was rough walking that first day, the board tucked under my arm and a heavy suitcase in each hand. I could handle them fine dragging them around the house, but carrying them across the street from our trailer and down into the woods was a lot harder than I’d counted on. By the afternoon, I was soaked in sweat and had to take off the aviator cap. I sat on a rock and opened both suitcases, wondering how to lighten the load. I drank the kool-aid and left the thermos by the rock. I left the pillow there, too — what had I been think? I would sleep on my rolled-up jacket like I’d always planned — and after a long consideration, flipping through the pages and considering the scrapes I might get into compared with the adventures of the Hardy Boys, I left behind two of the three books I’d brought.

The suitcases were a bit lighter then, but they were still each half my size and cumbersome as hell to lug around in the woods, so by the time it grew dark I hadn’t even made it to the first backroad I’d hoped to find. I sat on my skateboard in the hard dirt, no rocks in sight, and used the flashlight to look at my map from the atlas. It was huge, but so was North America, and peering in the dim light down at Texas, that little speck just northwest of San Antonio where I’d started out from, I figured I should have reached Amarillo by then, or at least Lubbock, but if that were true, I would have had to cross at least one of the bright blue highways marked on the map. I was still in the middle of nowhere.

For a while, yes, I wanted to cry. Maybe I did a little — I’ll admit it. I worried about how much I’d miscalculated, how much heavier the bags were and how much further I might have to walk. Eventually I would try hitching rides, sure, but I needed to get far enough away to do it, at least out of Texas. And now I wondered, too, how long my granola bars would last, though I still had the fifteen dollars.

When it got really dark and I switched off the flashlight — better not to risk a fire, and it was still warm enough, though a breeze was picking up — I looked around in the night and discovered lights through the trees. For a long time I huddled between the upright suitcases like walls, flinching at every twig snap and bird call, because I had no idea what those lights might be. But after several minutes I heard a door open and a man spit and a trash can lid bang, and I knew I was in some neighborhood. I almost switched on the flashlight to check the map again, but then I realized that this close to people, I might draw attention, and maybe someone would send me home again. Still, it felt good knowing I remained in the midst of civilization, just in case.

I opened one of the cases and balled up my jacket and slept in the dirt.

When I woke the next morning I was wet and itchy, balled up underneath the heavy wool blanket but still shivering in the cold. A front had moved in overnight. Later, I learned to recognize the patterns, that a final sharp cold front always pushed through Texas around Easter, but this was my first direct experience with it. I pulled on my jacket, twisting like an escape artist under the blanket, and then I poked out one blue hand to feel blind through the luggage for the aviator hat and goggles, and I pulled them on under the blanket, too.

I stayed under the blanket for a few hours, I think, waiting for the sun to rise high enough to warm me, but before I had decided to try peeking outside, I heard heavy breathing out in the trees and I pulled my knees into my chest. I held my breath, listening hard, trying to figure out who might be approaching. I thought of the man the night before. I thought of police. I thought of those perverts my mother worried about out on the highway. If I were a pervert, I’d probably stay away from the main highways, actually — I’d hunt the woods, looking for stupid kids who couldn’t read a map right and had just a pocket knife for protection.

I pulled the knife from my pocket and opened the long blade, just in case.

When the blanket moved I thought I would scream or kick out against my attacker, lash expertly with the knife, but instead I curled up tighter, like I might swallow myself and just disappear. The blanket slid off me and I felt the hot breath on my cheek, rank and wet, and then a tongue across my cheek. I squirmed away and rolled to my knees and this dog was just staring at me, panting and stupid with his tongue out, his breath in little puffs of fog. I cussed, and then I laughed a little. The dog was nosing into one of the suitcases, the one with the granola bars, but I stood shooed him away and then packed everything up.

With houses so near, I decided to risk the road, at least until I could get my bearings, so I headed up toward where I’d seen the lights the night before and found a back yard, then a house, and then the rough old asphalt road. I stayed in the back yards for a while, following the road at a distance the way you might follow a river. I heard cars out on some larger road and I walked that direction. When I came out of the trees I was on the access road beside the highway. I looked up and down the access road, trying to find a sign, some locator to tell me where to look on the map. I set down my suitcase and skateboard, which is when I realized I’d left the other suitcase back in the woods. I turned quick circles, panicking a little, then I ripped open the suitcase — it was the one with the key — to see what I still had and what I’d lost. I’d left behind the bottle of water, the granola bars, the extra clothes. I still had the map and the books and the eating utensils and a few other things, but like a damned idiot, I’d left behind the blanket. It was a bit warmer now in the sunshine, but I knew when night fell I’d want that blanket.

I was screwed. Even with the fifteen dollars in my pocket, I couldn’t buy a new blanket and enough food to get me to Canada.

I sat on the suitcase and thought. I looked up the access road, down it. I wanted to say parts of the road looked familiar, but I wanted just as much to say I was in foreign territory, another country even. For all I knew I’d headed south instead of north and might be in Mexico by now, which wouldn’t be so bad if this was the weather I had to look forward to. But then I saw the sign for the city lake, and I knew I was less than two miles from my house.

I looked at the road, I looked at my skateboard.

I’d come so far, but I’d gotten nowhere.

I just wanted to be free, to get away from my trailer and everything bad that had ever happened there.

But I was starving, and as my mouth watered and I reached for a granola bar I knew I didn’t even have, what I really wanted was cinnamon rolls. Warm, gooey, fresh from the can to the oven.

I stood up and lifted the suitcase, but my arms were tired, I was hungry, and let’s face it, hopeless as my grand adventure had been, I didn’t really need anything in there anyway. Even the Hardy Boys book — what had I ever learned from them?

I left it there in the road, and I walked out onto the asphalt and aimed my skateboard south back toward home. My legs were wobbly, my ankles tired.

To heck with it, I thought, and I lay down on the board, belly first, my head aimed toward home. I started swimming along the asphalt, pulling myself along, slowly for a while but then I hit a shallow decline and started picking up speed, no arms needed. The wind was so cold on my face that my eyes started to water, and I pulled the aviator goggles over my face. When I reached for the road again I was rolling too fast to touch it, gravity doing all the work, and my hands hovered over the blur of the asphalt. I held them out at my sides, palms flat and waving in the wind the way they did when I stuck my arm out the window of my uncle’s truck. They were lifting up on their own, that same mysterious force of the air that carried airplanes into the sky. I opened my mouth to the cold, cold air, a grin beginning in the lips, and I flew.

Well, that was unexpected. I hadn’t planned to write a whole short story when I started this exercise, but there it is. It’s not very good (yet), but it’s there, and maybe it could turn into something interesting, who knows.

Anyway, here’s the exercise: Like most photo exercises, I’m writing a story that I see in the pictures, but unlike most, I have two photos to look at, and what I’m supposed to do is consider them in dialogue with each other. The exercise comes from the literary journal Camera Obscura and is part of a small, regular contest they run called “Bridge the Gap.” On Camera Obscura‘s website, they explain the rules like this: “The current photographs above are the ingress and egress of a story born when these two images meet, celebrating the synergy of words and images. Take the reader on an unexpected journey from the image on the left to the one on the right in 1000 words or less.”

Okay, I broke the rules something fierce — my story is more than 3,000 words, not a mere 1,000! — but whatever. This wasn’t for competition anyway; the two photos I used were from an older contest, back in October 2010 (the winner was Marissa Coon, for her story “Runner,” and while I didn’t read her story before I wrote my own, I’ve read it since and it’s a great little piece — much better than my first attempt here! — so go read it online).

The deadline for the current “Bridge the Gap” contest is today, but keep an eye on Camera Obscura for the next pair of photos and take a crack at this yourself! I know I’m planning to give it a shot soon.

The chir of nighttime insects and the wide dark blue of the moonlight sky over the Texas Hill Country is not nearly as pleasant as a long, late-night conversation with my brother on our parents’ back deck.

The chir of nighttime insects and the wide dark blue of the moonlight sky over the Texas Hill Country is not nearly as pleasant as a long, late-night conversation with my brother on our parents’ back deck.