Oh, Ego, finding your doppelgänger online is only exciting if he isn’t several degrees cooler than you.

Oh, Ego, finding your doppelgänger online is only exciting if he isn’t several degrees cooler than you.

A Writer’s Notebook on hold today

Sorry, gang, but there won’t be a Writer’s Notebook post this week. I was all set to work on it this evening, but I had the news on in the background, and suddenly, with no fanfare and almost faster than I could notice, Omar Suleiman went on Egyptian television and announced that Hosni Mubarak has resigned as president of Egypt.

This is too huge, too historic, and I’m spending the rest of my evening focused on this.

I’ll catch up with you next week. I know you’ll understand.

Photo blog 41

“Grit.” In the desert near Sweihan, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 4 February 2011.

Believe it or not, these are not tilt-shift photos. They’re both naturally focused like this–I just rested the camera on the ground and let the autofocus do the rest. But I am as fascinated with the technique as I am with miniatures, and even though I’m nowhere near good enough to pull it off in real life, I’ve recently been playing with the technique of faking a tilt-shift photo in Photoshop. Below is a photo from the same desert excursion that I did Photoshop into a faux tilt-shift image:

Small stone, vol. 2, #1

The zest from my orange perfumes my mustache.

A Writer’s Notebook: Poetry-to-prose revision

For this exercise, I’m taking an old poem (which I don’t much like) and turning it into a piece of flash fiction (which I like only slightly better). After that: why I did it.

A Long Distant Line

I am reminded of my dad’s woolen Boy Scout blanket,

fuzz balling across it like mold, laying lumpy across

the field I see as I rest my prepubescent palm

against the painted gray barrel of this old cannon.

Across this rippled drag of lawn

a row of blue matches, aims at me.

I am eleven, unafraid.

The narrow muzzles—too small for the great

steaming cannonballs I had imagined the whole

car trip here—some history student, some intern

cemented long ago. The boy I am is disappointed;

I long to see one thin muzzle

heavy with iron instead of cement

fire, flame and acrid smoke and hissing ball

spit forth across the blanket field. I want the acid stench,

gunpowder burning, the rebel yell in my ears, blood,

the paint-red blood I’ve seen in films. I have come to see

the history once flat on a textbook page, now aimed

at my face. I will move on—giddy

with my grandparents in their station

wagon, me sprawled in the open back,

staring at the thin lines of the heater in the glass—I will

visit other places. Forests brackish green in North Carolina,

the sinking Washington monument, lost hazy days

through a foggy Tennessee. I will go home to my parents,

to my father of Boy Scout days,

my mother of classroom talk, I will

jabber youthfully about white-splattered statues,

echoing museums, silent cannon barrels. And later, when I am

grown, I will discover why they all—grandparents, mother, father,

cold statues on horses, swords drawn from stone scabbards—

why they all smiled sadly as I described the green blanket

fields in gray mornings and

the long distant line of cannon

blue aimed at me.

A Long Distant Line

Digging in the closet for the Uno cards. Boxes and dust. I found my dad’s old rug of a blanket from his days in the Boy Scouts, green balls of fuzz growing off it like mold. It reminded me of something, some other green.

The news was on in the living room. Friends arguing about the Middle East.

I dragged out the blanket, unfurled it across the bedroom floor, and stared at the ripples and folds it made. Something. Some memory.

Then:

The grass lays lumpy all across the field. I rest my prepubescent palm against the gray-painted barrel of the cannon next to me. Across this rippled drag of lawn a row of blue matches, tiny black irises staring mute at me from the distance.

I am eleven, unafraid.

Too small for the great steaming cannonballs I had imagined the whole car trip here—the narrow muzzles had been plugged into peace by some history student, some intern. Cemented long ago.

The boy I am is disappointed; I long to see one thin muzzle, heavy with iron instead of cement, fire into the green summer. Flame and acrid smoke and hissing ball spitting forth across the blanket field. I want the acid stench, gunpowder burning, the rebel yell in my ears. Blood, the paint-red blood I’ve seen in films.

I have come to see the history once flat on a textbook page, now aimed at my face.

I will move on, giddy with my grandparents in their station wagon, me sprawled in the open back to stare at the thin lines of the heater in the glass. I will visit other places. Forests brackish green in North Carolina, the sinking Washington monument, lost hazy days through a foggy Tennessee. Then I will go home to my parents, to my father of Boy Scout days, my mother of classroom talk, and I will jabber youthfully about white-splattered statues, echoing museums, silent cannon barrels.

And later, when I am grown, I will stand not in a dewy morning field but in my own bedroom closet, a deck of cards in my hand. Then I will discover why they all—grandparents, mother, father, cold statues on horses, swords drawn from stone scabbards—why they all smiled sadly as I described the green blanket fields in green summer mornings and the long distant line of cannon blue aimed straight at me.

This is an old exercise, one I’ve used successfully before (my story “Consuela Throws Her TV Away,” which appeared in Orchid back in 2002, started life as a poem). The idea is that changing forms changes the way we think about a piece: changing from poetry to prose helps us uncover some of the deeper ideas and underlying story in a poem; changing from prose to poetry helps us hear the rhythms of our language and experiment with richer imagery. A friend and early mentor of mine, David Breeden, used to turn his novels into screenplays just to tighten up the story and the language before he switched it back to a novel, and he turned his screenplays into novels in order to expand the story and explore character development in the script.

Changing forms of writing is a great revision tool, but what makes it especially cool is that we sometimes discover (as I did with “Consuela”) that the new form is the better form.

For one version of this and other revision exercises, check out the list on the Introduction to Creative Writing blog.

Photo blog 40

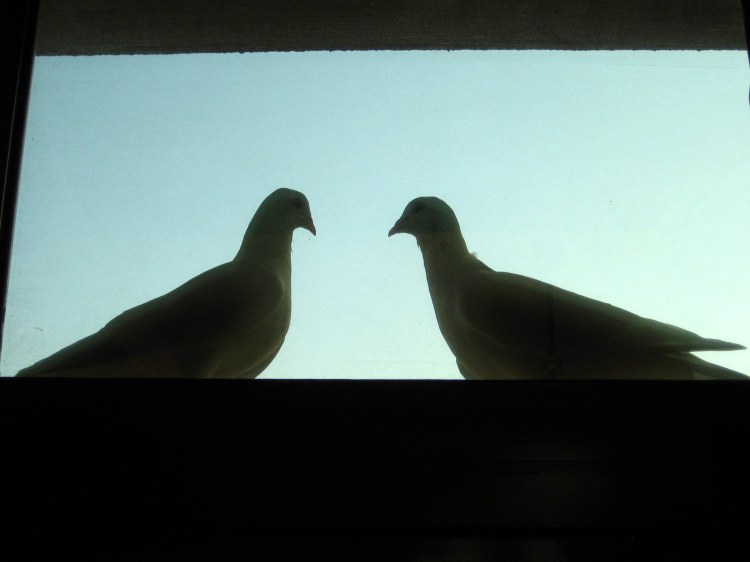

I post this as a prayer for a return to peace and for nonviolent, democratic progress during these turbulent days in Egypt.

Small stone wrap-up

So, I’ve finished the January “River of Stones” project. It’s been a lot of fun and, I think, good for my process–writing just this little bit every day, and paying careful attention to the words I’m putting down, has made me a more careful reader and even thinker as well as a more careful writer. It’s also been difficult–several times I have had to rush to the computer and squeeze in the writing at the very last minute, even on days when I’d already composed my small stone in my paper notebook earlier in the day.

I think I will continue writing and posting small stones, but I don’t think I could reliably sustain it every day. So I’m going to make it a weekly thing, like my Writer’s Notebook and Photo blog. Let’s say I post one every Monday.

So next Monday, look for the next small stone.

If you want to read the 31 stones I wrote in January, you can check out the “River of Stones” category, or just click over to Page 2 of this post and see them all in one place.

11-11: Aussie fiction review (Tim Winton)

I recently finished the first Aussie novel I’ve ever read, Tim Winton‘s Breath. Though it works within a frame of a middle-aged paramedic recalling his life, it’s mostly a Bildungsroman centered on extreme surfing in the `70s. Lots of hip, daring people chasing down hip, daring dreams as a means of self-discovery. But it’s far better than that summation makes it sound, and thanks to a fairly haunting opening with a teen’s accidental suicide during autoerotic asphyxiation, and hints of darker moments to come later in the novel, there’s a far more serious undertone (or undertow?) than the surfer narrative would at first suggest.

I recently finished the first Aussie novel I’ve ever read, Tim Winton‘s Breath. Though it works within a frame of a middle-aged paramedic recalling his life, it’s mostly a Bildungsroman centered on extreme surfing in the `70s. Lots of hip, daring people chasing down hip, daring dreams as a means of self-discovery. But it’s far better than that summation makes it sound, and thanks to a fairly haunting opening with a teen’s accidental suicide during autoerotic asphyxiation, and hints of darker moments to come later in the novel, there’s a far more serious undertone (or undertow?) than the surfer narrative would at first suggest.

In terms of style, the book at first reminded me of some kind of bizarre hybrid of Chuck Palahniuk and Kazuo Ishiguro, as though the self-appointed king of late-`90s hyper-masculine hipness had been tasked with writing Never Let Me Go — or vice versa. You wouldn’t think such divergent voices could operate in the same book, but Winton’s style (which rapidly shucked my initial associations to become Winton’s alone) expertly balances a strong, masculine voice with tender reminiscence, and it makes for beautiful reading. His passages describing the West Coast of Australia and the exhilaration of surfing are particularly well written.

There’s something about the pace that feels a bit off, and what is supposed to be the big revelation and climactic moment in the novel feel too far removed from the hints that were meant to prepare us for it. And the last lines feel a bit forced, as though Winton felt the need in the final paragraph to overtly spell out some Grand Theme for the novel even though he’d already done a fantastic job of suggesting that theme throughout the book, even from the first pages.

Still, it’s a great read, and I will definitely be picking up more Winton in the future. Also, when I looked up a bit about the man, I was thrilled to discover how much he supports young writers, including lending his name to the Tim Winton Young Writers Award for kids in Perth.

For more about my 11-11 project, check out my initial post on the challenge or all the posts in my 11-11 category.

For more on what I’m currently reading, check out my Bookshelf.

Small stone #31

Winds career over the rooftops, rending the rain-tarps in long shredded strips, flaying sections from the tin. The dust from construction down the street awakes and lifts from the sand and rock, filling the air like a city-sized, ponderous spirit. Out in the Gulf a storm floats past, but here in the city, we hear only the echo.

I’m participating in the River of Stones project in January. Look for a new post each day. Click the badge at left for more details.

I’m participating in the River of Stones project in January. Look for a new post each day. Click the badge at left for more details.

Small stone #30

Each eye feels punched in, my temples tight, my neck old rubber like an antique bicycle tire. All this news coverage, but so hard to turn away from it when the people I’m watching on tv or on the Internet refuse to turn away themselves. They face a wild and uncertain future, but they face it tenaciously, with hope and courage, and what can I do but watch them? How could I refuse to bear witness?

This stone is dedicated to the people of Tunisia, and Egypt, and Sudan; to the people of Algeria and Jordan and Lebanon and Yemen; to people everywhere, and whatever future they freely and peacefully choose for themselves.

I’m participating in the River of Stones project in January. Look for a new post each day. Click the badge at left for more details.

I’m participating in the River of Stones project in January. Look for a new post each day. Click the badge at left for more details.